Rev. Jeric Yurkanin.

First before we start the blog: We believe in taking the Bible as a guide—not as perfect “truth,” and not as a flawless, God-inspired book.

Anything humans touch, copy, translate, edit, and pass through the hands of kings and the most powerful people is going to be shaped by power. And that’s exactly what happened. This book has helped produce a multi-billion-dollar industry, and it has also become a tool for fake, self-serving politicians and pastors to use religion to gain favor, collect votes, and build platforms. And for many of them, money isn’t a side effect—it’s the agenda.

Religion can give people a way to excuse bad behavior, avoid accountability, and stay blind—because once someone believes “God is on my side,” they stop questioning themselves. They stop listening. They stop reflecting. They stop caring about the damage they cause, because they’ve convinced themselves it’s righteous. We believe in loving thy neighbor as thy self and be compassionate and empathetic and kind as a good human. So We see that blindness in politics every day—right now—and we’ve seen it throughout history.

Here start of my blog:

Let me share something that a lot of people feel but are scared to say out loud: having ICE walking around with guns like it’s a military state doesn’t make people feel “safe.” It doesn’t calm the nervous system. It doesn’t build trust. It doesn’t create stability. It creates trauma. It creates fear. It creates hypervigilance. It creates that constant sense of “something bad could happen at any moment,” especially for communities that already carry histories of being targeted, blamed, and treated like suspects before they’re treated like human beings. When enforcement is performed like theater—arms, intimidation, raids, breaking into homes—it doesn’t just “enforce law.” It communicates a message: power is here, and you are at its mercy. That message imprints itself in bodies. It shows up as anxiety, insomnia, panic, depression, and long-term distrust of institutions. And when I see people celebrating it, cheering it on, calling it “justice” or “order,” I can’t help but notice something deeper going on—something that has been going on for a long time in this country. America has always had a relationship with fear and control. We’re obsessed with it. We sell it. We market it. We run campaigns with it. We feed on it. We build policies with it. We turn it into entertainment. We turn it into identity. And American evangelical Christianity, for a long time, has learned how to profit from that same fear: grow numbers, gain influence, raise money, demand loyalty, and call it “revival.” Looking back from the 1500s to today, you can see patterns—fear-based preaching, fear-based conversions, fear-based community control, fear-based politics, fear-based moral panic. Some people treat that like a conspiracy theory, but honestly you don’t need a conspiracy. You just need a system that rewards fear. Fear gets attention. Fear gets obedience. Fear gets donations. Fear creates urgency. Fear creates “us vs. them.” Fear creates tribes. And a fear-based religion doesn’t have to be true to be effective; it just has to be emotionally addictive. It only has to give people a sense of certainty, a sense of superiority, and a sense of belonging—and then it can justify almost anything as “God’s will.”

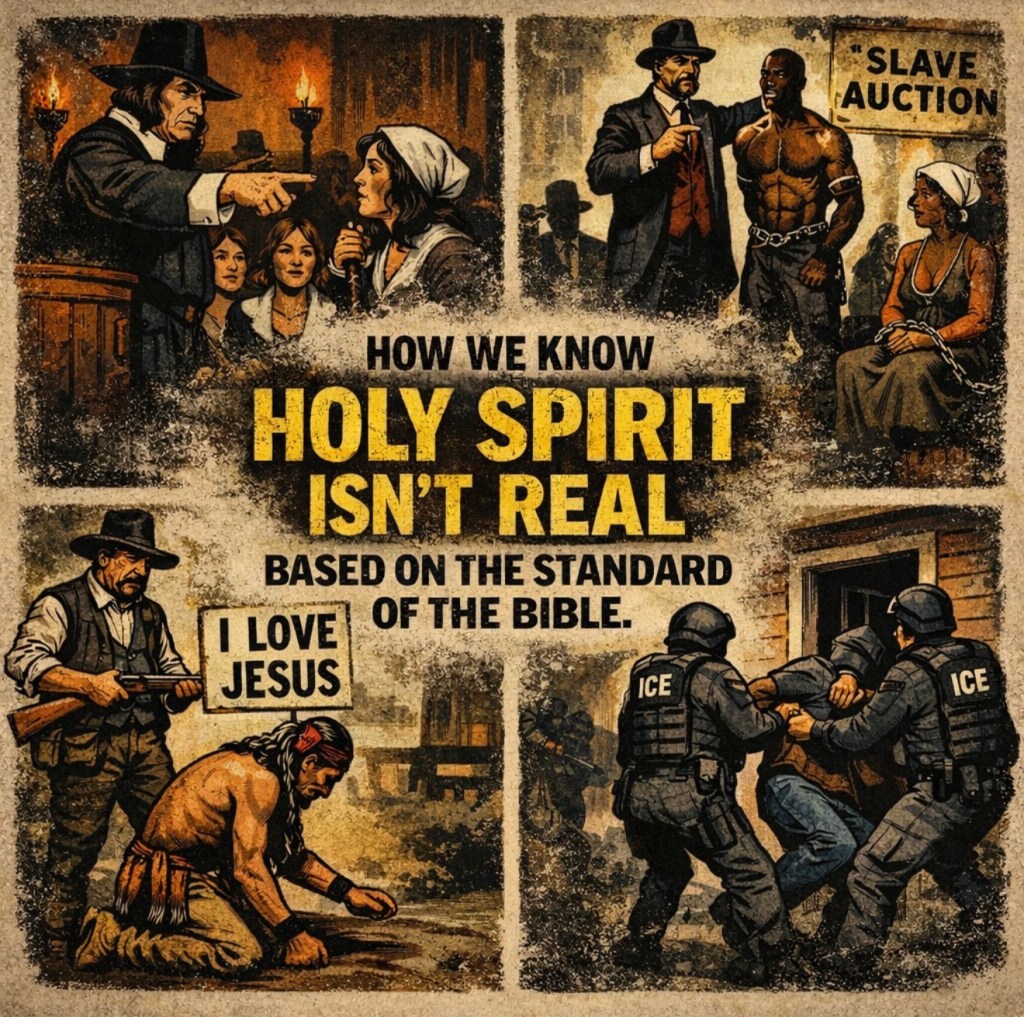

And that’s where my question comes in, because I’m not even starting from outside the faith. I’m starting from the Bible’s own claims. The Bible itself gives a supposed “standard” for identifying Jesus’ people. It’s not vague. It’s not complicated. “By their fruit you will know them.” “They will know you are my disciples by your love.” The fruit of the Spirit in Galatians 5 is presented as visible evidence of God’s presence: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control. If those are the standards, then we should be able to look at outcomes and ask a basic question: does this movement consistently produce love, patience, kindness, peace, gentleness, and self-control, or does it consistently produce rage, fear, shame, scapegoating, obsession with punishment, political domination, and a constant need for enemies? Because if the Holy Spirit is real in the way the church claims it is, you would expect a consistent direction. Not perfection—nobody is perfect. But a consistent pattern. A consistent tone. You would expect the loudest, most passionate “Bible-believers” to be the most loving, the most humble, the most merciful, the most emotionally grounded. You would expect them to be the safest people in the room, not the most threatening. But what so many people actually experience is the opposite. And that’s not just a random complaint. That’s evidence. That’s observation over time. That’s pattern recognition. So this isn’t simply “I’m mad at the church.” It’s not a petty rant. It’s a direct confrontation with a claim: if the fruit is consistently rotten, maybe the tree is not what it claims to be.

Let’s be honest about what a lot of people experience inside fear-based Christianity, especially in American evangelical culture. They experience a constant low-level anxiety about whether they are “right with God,” about whether they prayed the right prayer, believed hard enough, repented enough, surrendered enough, meant it enough, performed enough. They experience shame as the default emotional climate, like shame is not something you occasionally feel but something you live inside of. They experience an obsession with sin—especially sexual sin—as if the primary moral concern of the universe is what consenting adults do with their bodies, while greed, exploitation, racism, violence, and neglect of the poor become footnotes. They experience confession without healing, because confession becomes a ritual of guilt management, not an actual path toward emotional maturity. They experience rules without compassion, certainty without humility, authority without accountability. They experience anger disguised as righteousness, emotional immaturity disguised as “boldness,” manipulation disguised as “conviction,” punishment disguised as “love,” control disguised as “spiritual leadership.” And then there’s the political side, which is impossible to ignore now: the need to dominate public life, the need to legislate morality, the obsession with “taking the country back,” the craving for strongmen, the willingness to excuse cruelty if it serves the tribe, the endless hunger for scapegoats, the need to label outsiders “evil” so the group feels holy. For decades, people have been trained to measure spirituality by how loudly you condemn others, how certain you sound, how strictly you enforce rules, how aggressively you “stand against the culture.” But if you measure spirituality by the fruit of the Spirit, a lot of the loudest leaders fail the test immediately.

One of the most revealing things is how often Christians excuse cruelty with the line, “Well, we’re all sinners.” Yes, we know. That’s not new information. But the way it gets used reveals the game. “We’re all sinners” becomes a convenient escape hatch. It becomes a spiritual loophole: if a celebrity pastor lies, “we’re all sinners.” If a leader abuses power, “God uses imperfect people.” If a political figure behaves like a monster, “none of us are perfect.” If the church causes trauma, “people are flawed.” If Christians act hateful, “they’re just human.” Yet the same people who excuse abuse with “we’re all sinners” will turn around and destroy a LGBTQIA teenager’s life over “holiness,” shame women over bodies, shame people over divorce, shame people over questions, shame people over depression, shame people over doubt. So which is it? If “we’re all sinners” is supposed to produce humility, then why does it so often produce entitlement? If it’s supposed to create compassion, why is it used to defend power while punishing the vulnerable? That’s not humility. That’s a rigged system. That’s selective grace: grace for the powerful, law for everyone else.

After watching this for years, it becomes obvious what’s happening: Jesus becomes a cover story. Not a teacher. Not a model. Not a way of life. A scapegoat and a brand. People treat Jesus like a permission slip. “Jesus forgives me, so I don’t have to change.” “Jesus died for me, so I don’t have to repair harm.” “Jesus covers me, so you can’t criticize me.” “Jesus is my identity, so I can act however I want and still call myself righteous.” But if Jesus becomes a brand instead of a way of life, Christianity becomes a costume you wear over an unchanged personality. And that is exactly what people are noticing now. A lot of Christianity is not transformation. It is performance. It is image management. It is tribal signaling. It is saying the right words, using the right phrases, holding the right political positions, and then calling that “faith.” And when that happens, the Bible turns into a weapon for controlling others rather than a mirror for confronting yourself.

Here’s the hardest part, and it’s the part that a lot of people avoid because it’s too honest: for many people, what they call “salvation” is actually untreated trauma plus tribal identity plus an emotional addiction to certainty. They don’t need another sermon. They need healing. They need counseling. They need emotional tools. They need nervous system regulation. They need self-awareness. They need trauma-informed support. But instead, the system trains them to call every uncomfortable emotion “conviction” and every outsider a “threat.” It teaches them to spiritualize anxiety rather than treat it, to call fear “discernment,” to call control “leadership,” to call superiority “truth,” to call arrogance “boldness,” to call emotional suppression “holiness.” So rather than becoming emotionally mature, people become religiously armed. And when people are armed emotionally—trained to fear, trained to hate, trained to see enemies everywhere—then of course they will be drawn to militarized policing and fear-based politics, because it matches their inner world. It matches their theology. It matches their nervous system.

This is why evangelicalism can pair so easily with violence and militarized control. It’s the same operating system: create fear, name an enemy, claim divine permission, demand loyalty, collect money, call it righteousness. If your religion is built on fear, you will always need enemies, because enemies keep the fear alive, and fear keeps the machine running. And once fear becomes your fuel, compassion starts to feel like weakness. Empathy starts to feel like compromise. Curiosity starts to feel like betrayal. Nuance starts to feel like danger. And the more afraid people are, the more they crave a simple story with a villain. That is the psychology of moral panic. That is the psychology of authoritarian religion. That is the psychology that celebrates raids, celebrates intimidation, celebrates “cracking down,” because it confuses domination with safety.

And none of this is new. Historically, Christianity didn’t just “influence” politics—it partnered with power. Around 300 AD, in the era of Constantine, Christianity became entangled with empire, and once any faith becomes intertwined with state power, it changes. It shifts. It’s not just about beliefs anymore; it becomes about order. It becomes about control. It becomes about hierarchy. It becomes about enforcement. When a religion gains political power, it tends to move from compassion to coercion, from care to punishment, from community to bureaucracy, from serving to ruling. And for centuries across Europe and England, church and state were fused—pushing laws, policing behavior, enforcing “order.” That obsession with control regularly spilled into violence: persecution, imprisonment, executions. This isn’t about saying every Christian was evil. It’s about acknowledging a pattern: when religion becomes a tool of the state, it stops being about liberation and starts being about obedience. And people who love control love a religion that can label their control “holy.”

Even in early America, you see the same pattern—white Christian men invading, killing, and stealing land from Native peoples, using the Bible to justify it, and then praising God afterward. That’s not a minor footnote. That’s a moral indictment of what happens when people believe God is on their side no matter what they do. It’s the same pattern we keep seeing: take what you want, call it destiny; commit violence, call it righteousness; steal land, call it “civilizing”; destroy cultures, call it “mission.” Sound familiar? And the pattern didn’t end. It just got updated. Because it’s not only a Christian problem; it’s a human problem: people will use whatever is sacred to justify whatever they already wanted to do. If they want land, they’ll use God. If they want power, they’ll use God. If they want control over women’s bodies, they’ll use God. If they want scapegoats, they’ll use God. If they want superiority, they’ll use God. And the most dangerous part is that once you believe you have divine permission, you stop listening to your conscience. You stop listening to empathy. You stop listening to the human consequences, because you’ve labeled your actions “holy.”

Events like the Salem witch trials in 1692 and 1693 weren’t random “bad moments.” They were the result of a Christianized moral panic, fear weaponized into public punishment. When a society believes “evil is everywhere,” when people are trained to see threats in outsiders, when anxiety is spiritualized, you get witch hunts. Sometimes literal, sometimes social. And modern witch hunts still happen, just with different names: moral panics, scapegoating minorities, demonizing entire communities, calling entire groups “groomers” or “demonic” or “satanic” because it gives the tribe a common enemy. It keeps the fear engine running. Different century, same operating system.

Now look at who keeps becoming the target, and how the targets shift depending on the era. In the modern evangelical world, LGBTQIA people have become a convenient “other.” Why? Because fear-based religion needs a visible enemy. It needs a group to point at and say, “That’s the problem. That’s why God is judging the country.” It’s a convenient script. If you blame a minority group, you don’t have to talk about greed. If you blame a minority group, you don’t have to talk about sexual abuse in churches. If you blame a minority group, you don’t have to talk about corruption, hypocrisy, exploitation, homelessness, racism, healthcare, violence, or the fact that Jesus talked more about money and religious hypocrisy than he ever did about what modern evangelicals obsess over. So the obsession reveals something: it’s not about holiness. It’s about control. It’s about anxiety management. It’s about keeping the tribe unified by giving them a common enemy. And it’s a tragedy, because real people get harmed—kids, families, human beings—while pastors build platforms and politicians build campaigns.

And that’s why the homelessness question matters so much. It’s a simple test of priorities. If the modern church were truly doing the work of Jesus, we wouldn’t have a homelessness crisis like we do. I’m not saying churches can solve every structural issue alone. I’m saying the gap between what Jesus emphasized and what churches emphasize is enormous. How many sermons scream about housing the poor, feeding people, forgiving debts, welcoming immigrants, freeing the oppressed, protecting children, dismantling hypocrisy? Compared to how many sermons scream about sexuality, gender, culture wars, “end times,” political candidates? The priorities show the fruit, because what a movement obsesses over is what it worships. If you can get people to obsess over “culture war sins,” you can distract them from the sins that cost money to fix. You can distract them from confronting greed, exploitation, and systems that keep people suffering. And the tragic irony is that many churches will spend millions on buildings, lights, and production, while treating people sleeping outside as a background issue. That’s not “Jesus.” That’s branding. That’s an industry.

This is where my conclusion comes from, and it’s not meant to be edgy—it’s meant to be honest. If the Holy Spirit exists the way evangelicalism claims, and if the Bible is the clear standard that produces transformed disciples, then where is the transformation? Where is the love? Where is the peace? Where is the patience? Where is the gentleness? Where is the self-control? Not in theory. In reality. In the real world where people live. In the families damaged. In the communities traumatized. In the relationships broken. In the way the church responds to outsiders. In the way the church responds to the vulnerable. In the way the church responds to immigrants. In the way the church responds to queer kids. In the way the church responds to women. In the way the church responds to people who disagree. In my adult life, I have met some sincere Christians and some kind ones, yes. But the system as a whole—the machine, the culture, the political religion, the loudest version—does not line up with Galatians 5. It lines up with fear. And if the evidence doesn’t match the claim, we have every right to question the claim. That doesn’t automatically prove that nothing spiritual exists. It doesn’t automatically prove God doesn’t exist. But it does mean the evangelical story about “Spirit-filled discipleship” is deeply unreliable, because if the Spirit is active and powerful, why does the movement look like a fear factory?

Here’s the biggest reason it keeps happening: fear-based religion is effective. It works. Not spiritually—socially. Psychologically. Politically. Fear bonds groups faster than love does. Fear creates identity. Fear creates loyalty. Fear creates dopamine. Fear gives people the illusion of clarity. And once a religion becomes a system of power, it attracts certain personality types: people who like control, people who fear ambiguity, people who need certainty, people who want authority, people who want hierarchy. Then those personalities shape the culture to reward themselves, and the machine keeps reproducing itself. You don’t need to assume everyone is consciously evil. Systems can create evil outcomes even when individuals believe they are righteous. That’s the danger: the system can feel “holy” while producing harm, and because it feels holy, it becomes harder to challenge.

So where do we go from here? I’m not interested in replacing one control system with another. I’m not interested in becoming the kind of person I’m criticizing. I’m interested in something simpler, something more human. We need compassion. We need empathy. We need to relate. We need to understand people’s stories. We need to protect the vulnerable. We need to stop scapegoating minorities to avoid dealing with our own dysfunction. We need to stop using religion as a mask for emotional immaturity and as a weapon for political control. And yes, we also need boundaries, because love doesn’t mean enabling toxic behavior. Love doesn’t mean staying in abusive environments. Love doesn’t mean letting someone weaponize religion to control you. Love can be soft and strong at the same time. Love can say, “I see your pain, but I will not let you harm me.” Love can say, “I care, but I will not be controlled.” Love can say, “I’m listening, but I’m not accepting abuse.” Love can say, “I have compassion for you, but I won’t sacrifice my mental health for your comfort.” That’s not hatred. That’s maturity. That’s the kind of love that doesn’t pretend harm is holy.

A simple test for any belief system is this: does it make people more human? More compassionate? More grounded? More honest? More accountable? More empathetic? More emotionally mature? Or does it make people fearful, angry, self-righteous, and obsessed with punishment? Because if your religion makes you less compassionate, it’s not making you holy. If your religion makes you cruel, it’s not making you Christlike. If your religion makes you addicted to enemies, it’s not making you free. If your religion makes you excuse abuse as “sin,” it’s not making you healed. And if your religion celebrates traumatizing communities through intimidation and militarized enforcement, then whatever spirit is driving it, it is not the spirit of love.

This matters right now because we’re not talking about abstract theology; we’re talking about human consequences. When people celebrate raids, celebrate intimidation, celebrate families being torn apart, celebrate communities living in fear, this isn’t just “politics.” This is trauma. Trauma doesn’t disappear when the news cycle changes. Trauma lives in the body. Trauma shapes families. Trauma shapes communities. Trauma becomes generational. And if a religious movement cheers trauma because it feels like “justice,” that tells you what spirit is driving it. Because it’s not the spirit of love. It’s the spirit of fear, control, and domination—the same operating system that has repeated itself across centuries, dressed up in new language each time.

The deepest irony is that evangelicals claim they’re the “Bible people,” but the Bible’s own standard is the one they fail. “By their fruit you will know them.” “They will know you are my disciples by your love.” Love was supposed to be the standard, not fear. Compassion was supposed to be the evidence, not control. Healing was supposed to be the result, not trauma. So I’m not even demanding everyone abandon faith. I’m not telling people they have to become atheists or agnostics. I’m saying stop lying about what this is. If it’s not producing love, stop calling it Jesus. If it’s producing fear, scapegoating, cruelty, obsession with punishment, and political domination, call it what it is: a fear machine. And the fruit is the evidence. We need compassion. We need empathy. We need boundaries. We need accountability. We need trauma-informed healing. We need to stop using religion as a cover story for emotional dysfunction and as a weapon for control. Because love was supposed to be the standard. And the fruit was supposed to prove it.

Leave a comment