Written by: Rev. Jeric Yurkanin

Have you ever stopped and really looked at what “evangelical Christianity” in America has produced—not just in church on Sunday, but in personal life, public life, and the political alliances it defends? When you zoom out, a disturbing pattern emerges: American Christianity has repeatedly baptized the values of its era, then turned around and called those values “biblical principles.” And once something gets stamped “biblical,” it becomes nearly untouchable—no matter how unlike Jesus it is.

I know this world from the inside. I grew up evangelical, and I lived it as an adult for about fifteen years before I began deconstructing. I was taught that faithful Christians should support “the party that aligns most with biblical principles,” but I wasn’t taught to ask a more dangerous question: which party, which movement, and which candidates align with the teachings and spirit of Jesus in the Gospels? Those aren’t the same test, and American church culture has spent generations training people to confuse them—so loyalty feels like faith, and dissent feels like sin.

Because when Christians decide “God is on our side” and then go hunting for verses to prove it, history gets ugly fast. In the 1800s, American Christians defended slavery with Scripture—openly and confidently from pulpits—while other Christians opposed slavery with Scripture. Same Bible. Same God-language. Opposite moral outcomes. This wasn’t a harmless theological disagreement; it became a nation ripped apart in violence. Denominational history leaves receipts too: the Southern Baptist Convention was formed in 1845 in the context of conflict over slavery, and much later it publicly repudiated its historic ties to slavery and racism. That alone should permanently humble anyone who thinks “biblical principles” automatically equals “God’s will.”

Then came segregation, and the same “biblical” confidence marched right along into the 1950s and 1960s. Pastors preached that segregation was God’s design and that interracial relationships were sinful. When the federal government began challenging tax exemptions for racially discriminatory private schools, the fight became political and legal. The Supreme Court case Bob Jones University v. United States (1983) documented the policy of denying tax-exempt status to institutions practicing racial discrimination, including restrictions tied to interracial dating. And Bob Jones University didn’t drop its interracial dating ban until 2000—under intense pressure. That’s not ancient history. That’s modern America, and it shows how long the church can cling to a “biblical principle” until culture, law, and consequences force a retreat.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, the modern evangelical political machine solidified into what we now recognize as the Religious Right. The Moral Majority was founded in 1979 and helped mobilize conservative Christians into a dependable voting bloc. And as many historians have pointed out, the movement’s early energy wasn’t simply about “abortion” in the way people assume today; it was also entangled with backlash to desegregation and threats to segregated schools’ tax status, before abortion became the unifying moral banner. Around the same time, the Republican Party platform in 1980 explicitly included an abortion plank supporting a constitutional amendment to protect “the right to life for unborn children.” The point isn’t that Christians can’t care about abortion; the point is that the church learned how to convert selective moral language into political power while avoiding deeper self-examination about whether the fruit looked anything like Jesus.

And this “one-verse theology” didn’t stop with politics. It seeped into homes, parenting, and church culture itself. For decades, “biblical parenting” was preached in ways that normalized fear, control, and corporal punishment as spiritual obedience, amplified by influential voices like James Dobson and the evangelical publishing machine. Again, the issue isn’t that parents can’t discipline; it’s that the American church has a long history of turning a few cherry-picked verses into an entire culture of certainty—and then calling disagreement rebellion against God.

Even earlier than that, Christian language was used to justify conquest and the taking of Indigenous land. The Doctrine of Discovery traces back to 15th-century papal decrees that gave Christian empires religious justification to claim non-Christian lands and subjugate peoples, and its logic echoed forward into American legal history. U.S. Supreme Court decisions like Johnson v. McIntosh (1823) reflect how conquest-based assumptions shaped Indigenous land rights under American law. The assimilation era later left a documented legacy of trauma through government- and church-involved boarding schools that attempted to erase Indigenous languages and identities. So when people romanticize a “Christian America,” they’re often describing a story that, in practice, looked like conquest wearing a cross.

And here’s what makes this even more concerning: inside many evangelical churches today, preachers still frame the world like a simple story—Christians are the good guys, everyone outside is deceived, and there’s always an invisible enemy you can’t see but must constantly fear. You always need an enemy to keep a belief system advancing. Walk into a mega church and the lights, the stage, the drums, the guitars, and the emotionally engineered worship swell your heart until you think, “This is God. This is love. This is Christianity.” Meanwhile, most people in the room have never been taught honest church history in America or abroad—because that history complicates the sales pitch. When slavery and segregation get brought up, many leaders rush to protect the brand: “That wasn’t biblical,” “They were wrong,” “That was culture.” But if yesterday’s confident pastors were wrong, what makes today’s confident pastors automatically right?

That’s why I believe history will repeat itself. In 75 to 150 years, whatever version of evangelicalism still exists will likely look back at certain sermons, certain political alliances, and certain culture-war crusades from the 1980s through 2026 and ask, “How did they get that so wrong?” Just like we look back and ask how “Bible-believing” churches defended slavery, justified segregation, and preached it with certainty. The church keeps calling it “biblical” right up until the future calls it cruelty.

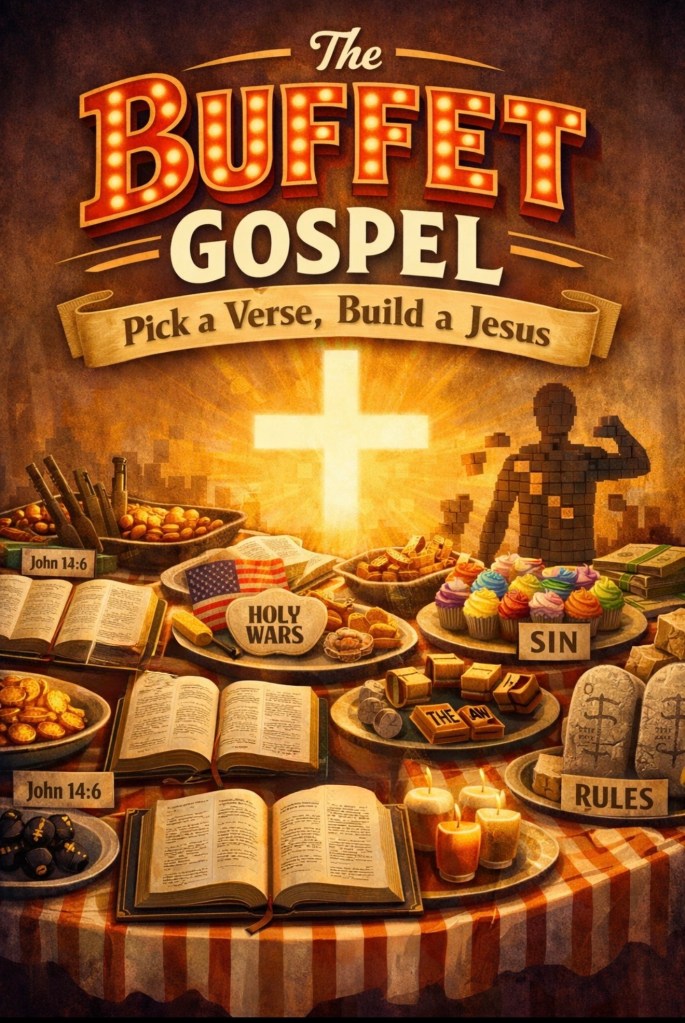

That’s also why the phrase “biblical principles” has become a smoke screen. Because once a community decides what it wants—politically, culturally, emotionally—it can almost always find two or three verses to justify it, while ignoring the weight of Jesus’ actual teachings. And the most alarming part is how curated the outrage has become. Certain topics trigger endless sermons, election panic, and boycott campaigns, while greed, exploitation, dishonesty, cruelty, abuse of power, and neglect of the poor barely register—even though Jesus repeatedly confronts money, hypocrisy, religious performance, and the way society treats “the least of these.”

So I’m left asking the question that should make everyone uncomfortable: when have American Christian nationalists and mainstream evangelical culture actually followed the Jesus of the Gospels instead of following their politics and their pastors? Because when you look at the receipts—slavery defended as “biblical,” segregation defended as “biblical,” conquest defended as “God’s will,” culture wars marketed as “holiness,” and institution-protection treated like discipleship—it starts to feel less like Christianity is “standing firm,” and more like it’s endlessly adapting to keep power, protect status, and keep money flowing.

And then comes the deepest contradiction: I’ve been told my whole life that God doesn’t change, yet the “biblical principles” being preached in America keep changing with the era. What was once taught as God’s design gets quietly revised when it becomes socially costly. What was once considered “clear Scripture” becomes “context” when it threatens the brand. The goalposts move, the certainty stays, and the people in the pews are expected to pretend nothing happened.

Meanwhile, many churches have turned Jesus into a sales pitch—a product to market, a brand to protect, and for some people, a form of fire insurance. They sell merchandise in the sanctuary and build entire systems around fundraising, expansion, and institutional survival, while the Jesus they claim to represent is the one who confronted religious profiteering and flipped tables when worship became a marketplace. And when pastors claim to speak for God, the congregation often treats them like the final authority, while the money people give doesn’t float up to heaven—it pays salaries, mortgages, production budgets, and the machinery that keeps the institution running.

So yes, people are leaving evangelical churches in massive numbers, and it’s not because they “just want to sin.” That’s one of the oldest and laziest sales tactics in the religious marketplace: blame the person who leaves so you never have to examine the product you’re selling. People are leaving because they found fear instead of love, control instead of honesty, hypocrisy instead of integrity, and leaders trained—often explicitly—to protect the institution at all costs. They’re tired of rehearsed answers meant to keep attendance high and donations steady. They’re tired of a Bible treated like it fell from the sky fully formed, with whole chapters ignored because they would raise uncomfortable questions. They’re tired of certainty being valued more than truth, and loyalty being valued more than character.

That’s a big reason I walked away from that system, and why I started Agape Freedom as an online church community—because we’re living in a different age now. Information isn’t locked behind pulpits anymore. People can verify history. They can read primary sources. They can buy a book, pull up court cases, study church history, and see how theology developed over time. The gatekeeping era is collapsing, and what was hidden for generations is harder to hide now. The American evangelical church isn’t “dying” because atheists are too powerful; it’s bleeding credibility because too many pastors and too many political alliances have betrayed the very Jesus they claim to preach.

So the question isn’t whether Christianity will change—it always has. The question is whether the American church will ever have the courage to stop building a Jesus that fits its culture, its party, and its revenue model, and finally return to the Jesus of the Gospels: enemy-love, humility, compassion, truthfulness, generosity, care for the poor, and justice that doesn’t depend on who’s in power. Because if it doesn’t, more churches will close, more people will walk, and it won’t be because they hated God—it will be because they got tired of being sold a version of Jesus that looks nothing like Him.

Leave a comment